Charging children as adults

A judge, not a prosecutor, should decide whether a child should be charged as an adult.

- 4 Minute Read

DC is one of only 14 jurisdictions in the country where a prosecutor can directly charge a child as an adult without a court hearing. Unlike those other jurisdictions, DC does not rely on its own locally-elected prosecutor to make those decisions. Instead, it is at the discretion of a federally-appointed United States Attorney. Because children who are treated as adults are more likely to commit a crime in the future, these decisions should not be made lightly. DC should change the law so that the court is allowed to hear from both parties and consider all relevant information before that happens.

What you need to know

Federal prosecutors can automatically charge youth in adult court.

In DC, up to age seventeen, most young people being charged with a crime would have their case heard in family court. There are two ways a child can be charged as an adult: the federal prosecutor directly files the case in adult court or the case is transferred from family court to adult court after a hearing that considers the specific facts and the child’s situation. In DC, if a sixteen or seventeen year-old is arrested for one of four offenses – murder, rape, burglary, and armed robbery – a federal prosecutor may directly file the charges in adult court. In these situations, the child has no opportunity to be heard, and there’s no way to undo the prosecutor’s decision. Once tried as an adult, a child cannot be sent back to family court. Washington, DC, is one of only fourteen places in the country where a prosecutor can decide, on their own, to directly charge a child as an adult.

The lack of a court hearing robs young people and the community of due process.

The District already has a transfer process through which prosecutors from the office of the locally elected attorney general can request a hearing before a juvenile judge. That judge would then make an informed decision about the appropriate court after hearing from both sides. By contrast, a former federal prosecutor said, direct file cases “were made quickly, sometimes in a matter of minutes,” were decided without a “concrete and vetted” policy, and were made by attorneys who did not specialize in youth cases.

The lack of local control affects the outcome of the process.

For these four crimes, the US Attorney’s Office – a federal agency that is not accountable to DC voters – can make the decision to put children in the adult criminal system. The process for every other young person handled by the Office of the Attorney General is totally different: local prosecutors have to provide evidence about why a child should be tried as an adult, the child’s lawyer has an opportunity to provide evidence about why that child should stay in family court, and the judge would make a decision after hearing both sides. The previous Attorney General worked with the DC Council to introduce a bill to end direct file and require the transfer process. Although it didn’t pass, the current Attorney General agrees that “kids are kids” and shouldn’t be treated as adults.

Experts and the public agree – the judge should make the decision.

One survey showed 82 percent of people prefer a court process with a judge making a decision whether a young person should be transferred, rather than a simple prosecutorial decision. And experts agree with the public. An in-depth review published by the National Research Council of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommended, “[E]ven for youth charged with serious violent crimes, an individualized decision by a judge in a transfer hearing should be the basis for the jurisdictional decision.”

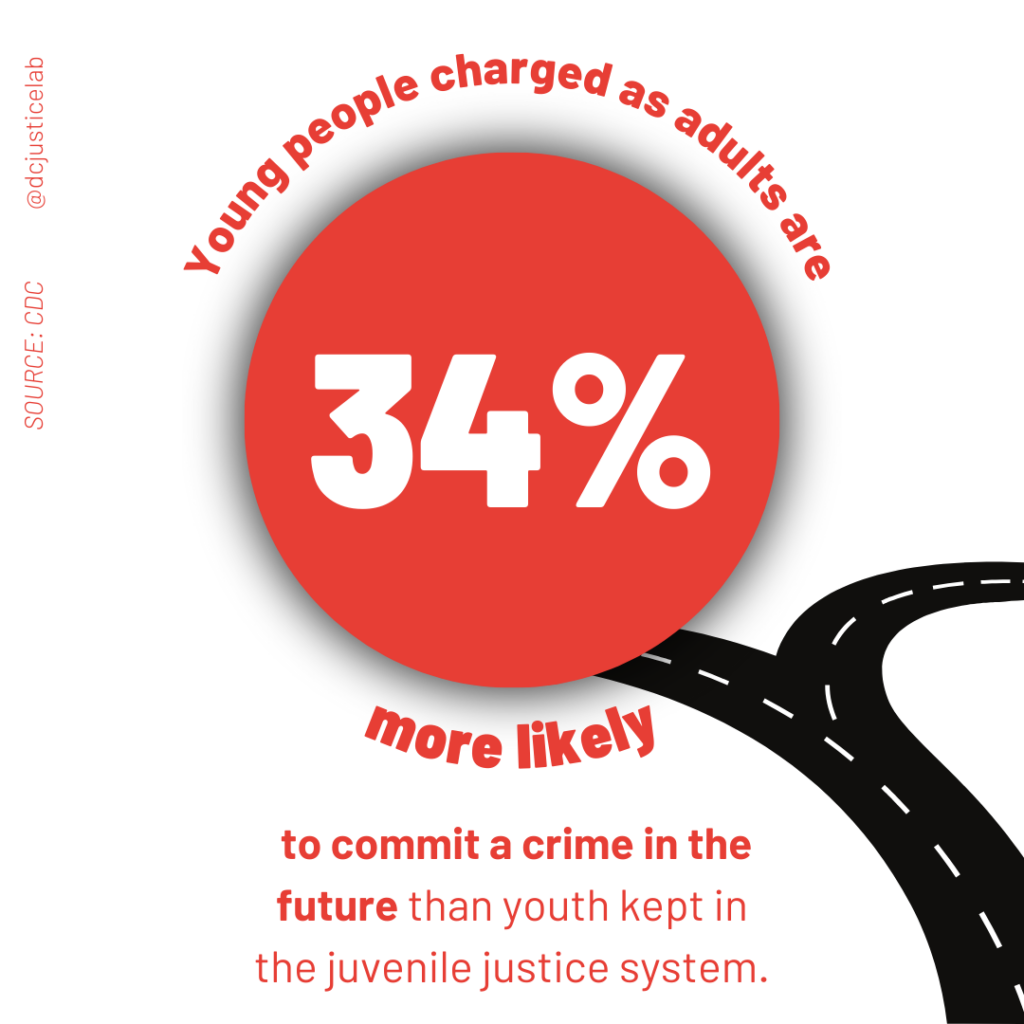

Transferring a young person to adult court reduces safety.

Young people tried as adults are 34 percent more likely to commit a future crime than young people kept in the juvenile system. If convicted, they may serve a sentence in a Federal Bureau of Prisons facility far from people and communities that can help them prepare for their return. Two-thirds of young people convicted as adults return by the time they are 21, after years in federal prisons that do not have the type of educational, vocational, and age-appropriate treatment and services necessary to help rehabilitate young people. Without those services and after years of being in prison far from any support, those young adults are much more likely to end up back in trouble, which makes the whole community less safe.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

Georgetown Juvenile Justice Initiative October 2021

DC Superior Court data analysis by The Sentencing Project October 2021

National Research Council of the National Academies of Science 2013

Former Attorney General July 2021

PBS Newshour July 2021

Campaign for Youth Justice

special thanks

Eduardo Ferrer