Consent searches

Consent searches are never consensual when compliance is a survival tactic.

- 4 Minute Read

Saying “no” to an officer when they ask for consent to conduct a search can involve serious risk of violence or legal consequences. DC has tried to increase protections for the community by requiring officers to explain that people can decline a search, but most people misunderstand these rights or waive them and are still vulnerable to coercion. Consent searches have almost exclusively been conducted on Black people and rarely result in the recovery of guns or evidence of a crime. Rhode Island, California , Oregon and Minneapolis have either already limited or are considering legislation to narrow the use of consent searches. DC should follow the lead of other places that have eliminated or dramatically curbed consent searches.

What you need to know

Consent searches allow officers to sidestep the usual process.

An officer can search someone or their property if they get a court to approve a search warrant. This requires the officer to show that there is a good chance they will uncover evidence of a past or active crime. If an officer asks someone for consent to search them or their property and that person gives it, the officer doesn’t need any other justification. They can skip all the usual investigative steps and conduct the search based only on that consent without any reason to believe that the person has committed a crime.

Consent searches are never consensual when compliance is a survival tactic.

True consent requires the freedom to say “no” without fear of punishment. In these situations, people who are the most vulnerable to police violence do not feel free to say “no.” Research shows that most Black people feel like they have no choice and want to appear compliant because they feel an underlying threat of physical or legal reprisals if they don’t consent to a search. People with disabilities, women, non-English speakers, children, LGBTQIA+ individuals, and others are also more vulnerable to police abuses and rely on compliance as a survival tactic. The Office of Police Complaints and the District of Columbia Court of Appeals have recognized the unequal impact consent searches have on Black residents in this city.

Consent searches do not improve safety.

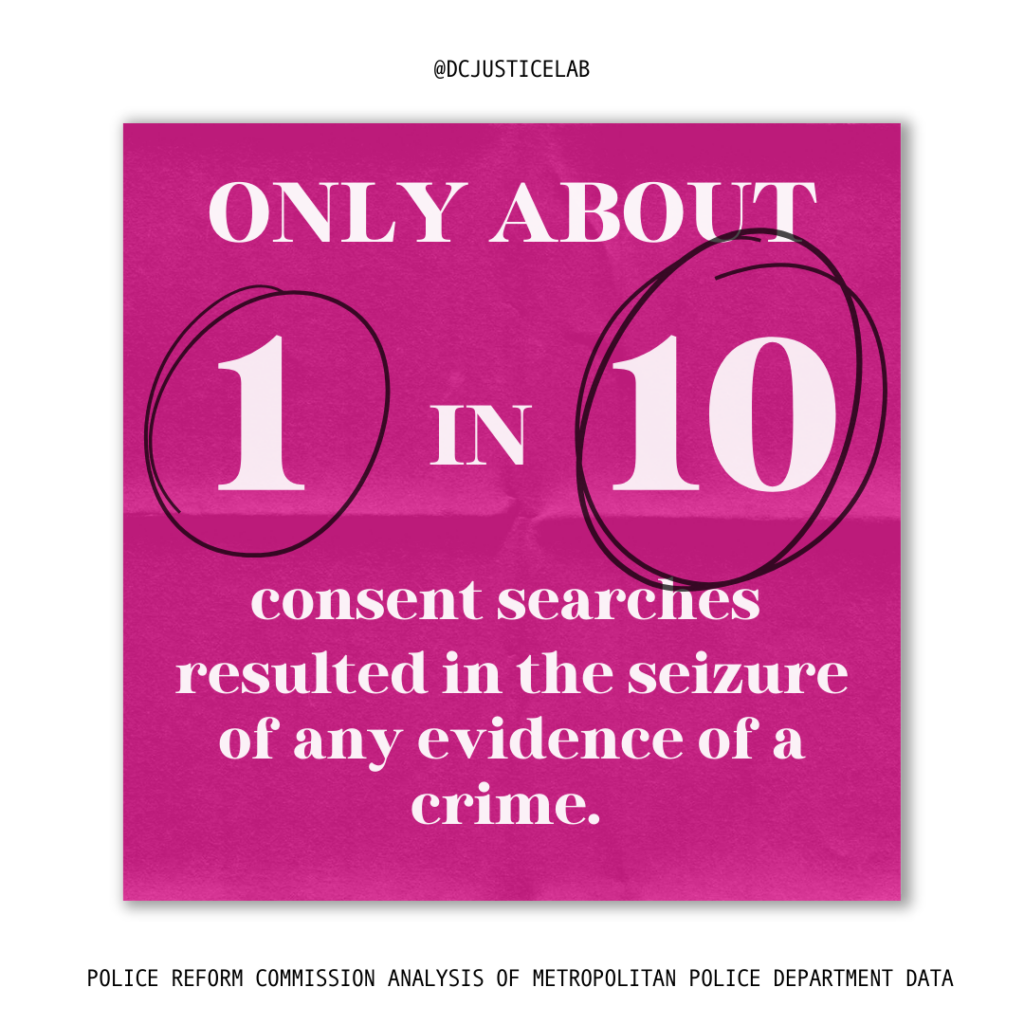

Consent searches not only fail to provide a genuine choice but also prove ineffective as a search tactic. Over an 18-month period in 2019 and 2020, the Metropolitan Police Department made 4,427 consent searches, but only 9.5 percent retrieved any evidence of a crime, and only 2.3 percent resulted in the seizure of a gun. Consent searches, even when repeatedly employed in a particular neighborhood or on individuals matching a specific stereotype, yield minimal evidence and erode public trust without enhancing safety. A recent study on the impact of consent searches in five states found “there is no discernible relationship between the use of consent searches and crime.”

DC’s reforms to consent searches don’t solve the problem.

Recognizing the problems with consent searches, DC changed the law to require that officers inform a person they have the right to refuse the search. The warnings are supposed to be similar to officers explaining the right to remain silent and other rights one is provided when arrested. But research shows that the most vulnerable people in need of protection from police are most likely to waive their rights, and most people don’t even understand their rights.

Other places are going further than DC to eliminate consent searches.

Multiple cities and states have taken steps to limit consent searches. Rhode Island banned consent searches conducted without reasonable suspicion or probable cause of a crime during traffic stops. Oregon also recently passed legislation significantly narrowing the consent searches during traffic stops. Minneapolis, Minnesota, is now working to prohibit consent searches during both pedestrian and traffic stops. Building on efforts where the California highway patrol unilaterally ended consent searches for a six month period, California lawmakers have also introduced a bill to prohibit consent searches. These changes are happening in other countries as well. Scotland reformed its practices around “stop searches” and dramatically reduced the practice, nearly to the point of eliminating consent searches.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

Journal of Empirical Legal Studies May 2022

Minneapolis, Minnesota Consent Decree March 2023

California Law Review March 2017

Southern Methodist University Law Review January 2012

Georgetown Law’s Center for Innovation and Practice, Howard University and The Lab @ DC

Howard University Professor Josephine Ross

Our Solutions

- Prohibit all consent searches

- Require the exclusion of any evidence obtained from a consent search

- Allow people to sue or recover or obtain damages if a search is deemed illegal

- Allow for a way to submit anonymous reports about officers who violate current consent search policy

special thanks

Kaylah Alexander ★ Josephine Ross ★ Leah Wilson