Mandatory arrests

Mandatory arrest laws deter some victims from reporting crimes.

- 4 Minute Read

DC requires that the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) make at least one arrest when responding to a domestic violence call. Forcing officers to make an arrest can make situations more dangerous, deter people from calling for help because they don’t want their loved one to get arrested, provide victims no support, and can actually increase harm for victims and their families. Research shows mandatory arrest policies do not increase safety or reduce domestic violence incidents, but do disproportionately impact Black women and their families. DC should join the twenty-seven states that have given discretion to officers to decide whether to make an arrest, and increase the use of co-response teams that provide victims with emotional support, crisis counseling, advocacy, and information about their rights.

What you need to know

Mandatory arrests in domestic violence cases are counterproductive.

A victim of domestic violence may call police in a moment of fear, with the intention to de-escalate the situation but not have their loved one arrested. Mandatory arrest laws may escalate a situation that could be resolved informally through other means. These laws may actually deter people from calling for help because they do not want their loved one to be arrested, convicted of a crime, and suffer all the consequences that come with that. Sometimes, they depend on their loved one for financial support, childcare, or shelter and do not want to risk losing them. On the scene, it can be difficult for officers to determine whose version of events is most accurate, and they sometimes arrest the wrong person or both people. Because of these challenges, twenty-seven states have decided that officers have the discretion to decide whether to make an arrest based on each individual case.

Mandatory arrests do not increase safety and can break up families.

A review of eleven studies found that mandatory arrest of an individual involved in a domestic violence case had no deterrent effect on the behavior, with some studies showing mandatory arrests actually increasing the risk of a repeat offense. A working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research found states with mandatory arrest laws have 60 percent higher rates of domestic violence homicides. And when parents are arrested, it can trigger a formal child welfare investigation, leading to a child or multiple children being removed from the home.

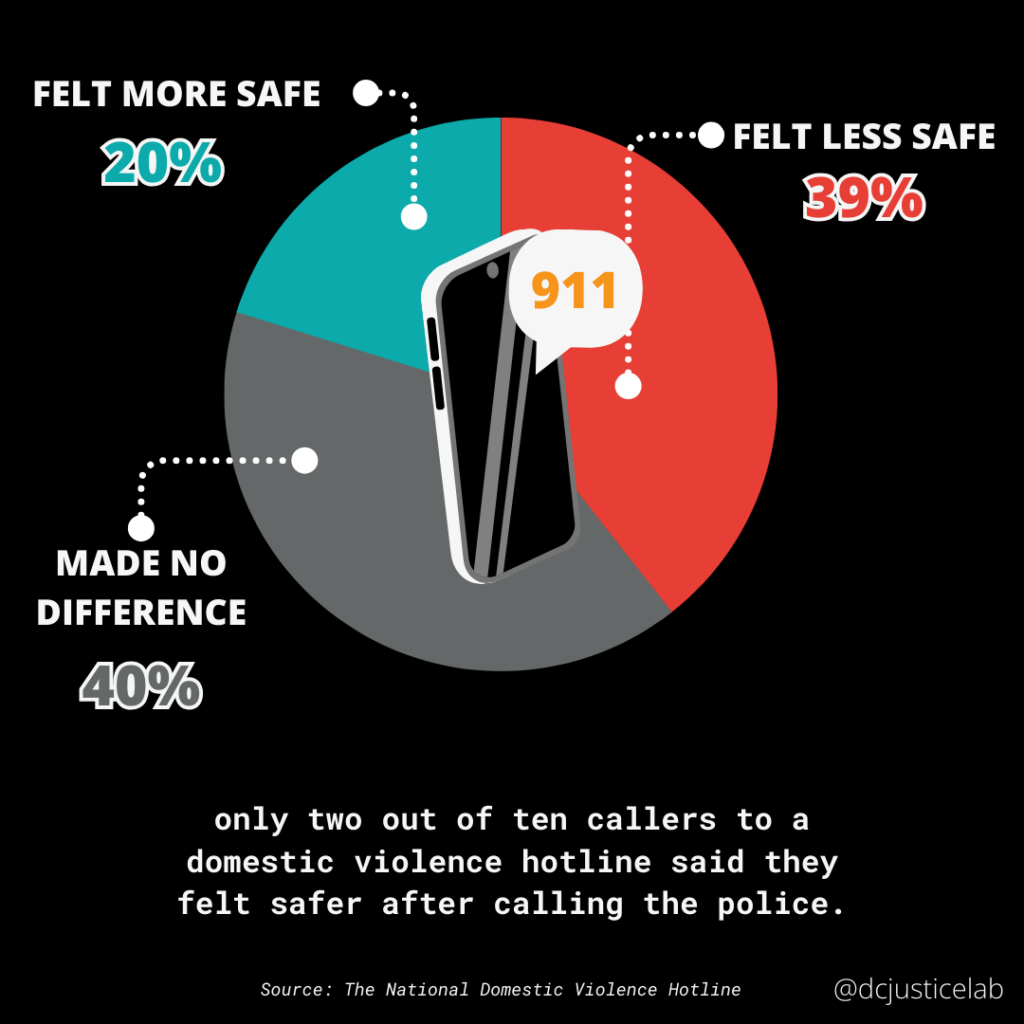

Victims say police don’t make them safer and other responses are needed.

Seventy nine percent of callers to a domestic violence hotline said calling the police either made no difference in their safety, or that they felt less safe after the call. Nearly four dozen domestic violence coalitions and service providers across two-thirds of U.S. states have called for reducing the role of police in responding to instances of domestic violence. The Coalition to End Domestic Violence has said that mandatory arrest laws have unintended consequences and published estimates showing these laws contribute to more people being victims of crime. The DC Coalition Against Domestic Violence said “while mandatory arrest laws were originally praised as being beneficial to survivors, these policies may have made survivors less safe and increased mortality rates.” As part of a larger victims’ rights bill, victims advocates changed the law so that someone can object to a hospital based violence intervention program sharing information with the police.

DC law is so broad that it includes behavior that should not result in an arrest.

In 2022, the MPD made 4,477 arrests for “intrafamily offense” —a category that is defined to include much more than violence against a domestic partner. For example, a nonviolent offense against a family member or housemate is treated as a domestic violence case in D.C. Writing a bad check or stealing an item from a roommate meets this definition. The crime category also includes every offense that can occur in this setting. For example, if someone writes a bad check for child support, technically, that is a domestic violence offense. The DC Police Reform Commission was told that police have been called to respond to nothing more than two siblings fighting over a slice of pizza.

Co-response models reduce the role of police in domestic violence cases.

Seventy one percent of callers to a domestic violence hotline said that if non-police resources had been available, they would have preferred to use them instead. Under a co-response model, police could be joined by an advocate whose job is to assess a victim’s safety, provide them with information about their rights, and connect them to a resource, service, or a social worker or crisis counselor. These types of co-responding models are expanding in Richmond, Virginia, and Los Angeles, California. DC Safe does something similar, but according to the Police Reform Commission, they only serve a small number of cases.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

DC Coalition to End Domestic Violence on mandatory arrest laws May 2021

The National Domestic Violence Hotline April 2015

DC Coalition to End Domestic Violence on mandatory arrest laws

ACLU Survey: October 2015

Institute for Women’s Policy Research October 2015

The Nation April 2023

Lenore Anderson in The Guardian

Our Solutions

DC Should:

- Repeal the mandatory domestic violence arrest law

- Narrow the legal definition of intrafamily offense

- Have co-responder advocates respond to domestic violence calls with police

- Increase funding for community organizations that respond with or instead of police

special thanks

Cassandra Hernandez ★ Olivia Blythe ★ Nada Elbasha ★