reparations

Reparations have the potential to reduce the racial wealth gap and increase public safety.

- 5 Minute Read

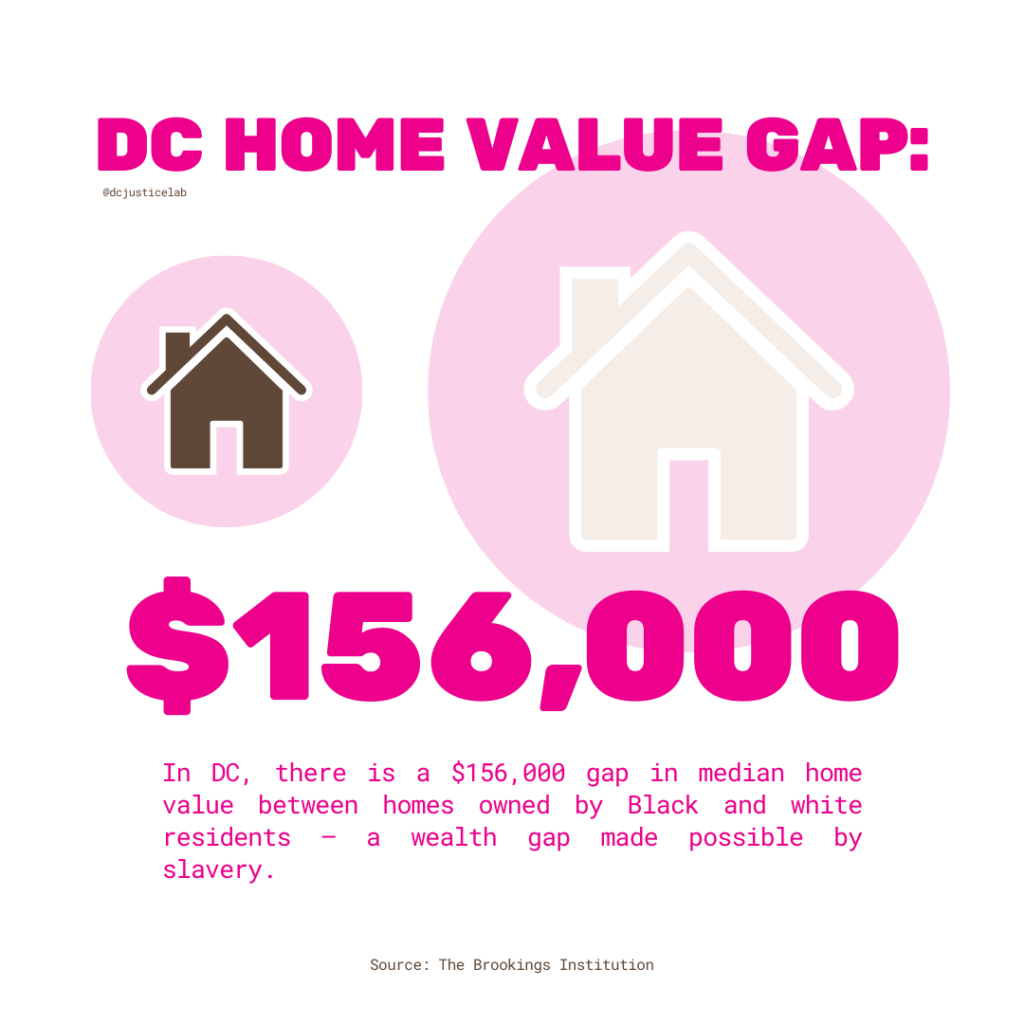

Researchers, government entities, and elected officials have acknowledged slavery and discrimination led directly to the health, housing, and wealth gaps between Black and white residents in the US. As a result of slavery and the policy decisions that followed in its wake, there has been a disinvestment in Black communities and the core drivers of safety that prevent violence.: one indicator of the scale of disinvestment is, white households in DC have 81 times the net worth of Black households. States like California and New York, and cities like DC, Evanston, Detroit, Providence, and Greenbelt have passed legislation to convene task forces charged with studying and making recommendations for repair.

What you need to know

Reparations to address past harm have a long history in America and internationally.

Reparations are measures provided to address harms from the past. According to the United Nations, there are five conditions that must be met for full reparations: (A) Restitution, (B) Compensation, (C) Rehabilitation, “(D) Satisfaction, and (E) Guarantees of non-repetition.

Reparations are not a new concept in the US or internationally. The United States has paid reparations to victims of the internment of Japanese-Americans in camps in World War II and to Indigenous people for the illegal seizure of their land. As part of the federal 1862 District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, which freed enslaved Black people in DC, enslavers were provided with compensation for their losses: the United States is the only jurisdiction that has provided compensation in this way to slaveholders. The federal government has provided compensation to people exposed to toxic chemicals by the government, like Vietnam Veterans exposed to Agent Orange, to the descendants of Black victims of lynching, and internationally, to Jewish victims of the Holocaust.

There are different perspectives on how reparations should be provided.

There are different perspectives on how much, who, and what types of reparations should be made. For some, such as members of American Descendants of Slavery (ADOS), those who are direct descendants of enslaved people should be beneficiaries. For those who have a Pan-Africanist view, like the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA), all Black people should be beneficiaries because if you have been living in America, as a Black person, you have most likely experienced racism and discrimination in one way or another. The National African American Reparations Commission has twice issued guidance on questions of eligibility and the types of reparations that municipal, state, and federal governments could provide. While economists have estimated that trillions of dollars are owed to descendants of slavery, most of the focus to date has been on studying and making recommendations to address the remaining policy issues around how much, and how reparations should be paid.

Federal, state, and local efforts for reparations have been building.

For 25 years, congressional leaders have introduced legislation in each session that would begin the process of making reparations. The most recent version of the bill garnered a third of the House of Representatives as co-sponsors. President Biden has been encouraged to issue an executive order to create a federal reparations commission before he leaves office. California and New York passed legislation to study, develop commissions, and make recommendations on how reparations should be paid.

Along with these states and the federal government, much of the activity around reparations has focused on local government bodies:

- Asheville: The Reparations Commission was empowered in 2022 to make short-, medium-, and long-term recommendations that will make significant progress toward repairing the damage caused by public and private systemic racism, and will issue a report with recommendations. The work of the commission is ongoing.

- Detroit: Instituted in 2024, the Detroit Reparations Task Force of 13-membes consisting of four executive members appointed by Council President Sheffield and nine general members. The task force will develop recommendations for housing and economic development programs that address historical discrimination against the Black community. Recommendations are expected to be sent to the city council in March, 2025.

- Providence: On February 28, 2022, Mayor Elorza signed a community-driven Executive Order establishing the Providence Municipal Reparations Commission to address the injuries outlined in an information-gathering phase and provide clear recommendations to the City on appropriate policies, programs, and projects to begin repairing harm. As part of the city’s COVID relief funds from the American Rescue Plan Act, the city council has allocated $10 million to organizations to “close the racial wealth and equity gap between Providence residents and neighborhoods.” The reparations plan does not include any direct payments to residents but focuses on funding programs such as job training, scholarships, and education.

- Tulsa: After the City Council of Tulsa passed a Resolution on the Tulsa Race Massacre, its passage instituted a project to provide a community-driven engagement process that identifies concrete pathways to repair issues. A Commission was instituted in August 2024 to begin the process on formulating recommendations on reparations, focusing first on addressing housing inequities in the city. The work of the commission is ongoing.

- Greenbelt: Through a referendum in 2021, residents of Greenbelt, Maryland directed the City Council to create a 21-person commission to review, discuss, and make recommendations related to reparations for African American and Native American residents of Greenbelt.

- Evanston became the first US city to administer reparations in 2021, which includes cash payments to help purchase property, housing repairs, and mortgage assistance. Evanston’s approach was expanded recently to include more recipients and increased direct cash benefits to individuals.

Reparations seek to address the policy legacy of slavery in DC.

Researchers, government agencies, and charitable foundations draw a direct line between the impact of slavery on its descendants and policy decisions that followed that led to wealth and health gaps between DC’s white and Black residents. One researcher ties the history of slavery in DC to the policy decisions that led to over-policing and mass incarceration in Black communities instead of policy choices that would have invested in schools, community centers, social services, health care, and violence prevention. Researchers say redlining, disinvestment in Black neighborhoods, and the War on Drugs are the aftermath of slavery that paved the way for gentrification: white households in the District have 81 times the net worth of Black households. DC has the highest percentage of gentrifying neighborhoods among large cities, which researchers say relates to, “decades of job and housing discrimination…. fostering a segmented work force hindering the ability of all African Americans to accumulate wealth — that invisible resource that can be a key mitigating factor preventing displacement.” If reparations result in new policies, such as payments to individuals at risk of violence or increased efforts to invest in Black residents’ health, education, employment, and housing opportunities, those approaches would increase safety by addressing the core drivers of instability.

Efforts to make reparations in DC have been building over the decades.

The establishment of Emancipation Day as a holiday in Washington, DC, in 2004 was, in part, a step toward acknowledging the impact of slavery in DC. Institutions like Georgetown University have also responded to their roles in slavery: Georgetown created GU 272, which provides preferential treatment to the descendants of the 272 enslaved people who the Jesuits sold to keep the university open in 1838. Proposals to convene experts, to study the issue, to support federal reparations efforts, and for DC to make reparations have been considered by the Council of the District of Columbia in 1990, 2000, and most recently in 2020.

DC has introduced and pre-funded legislation for a reparations task force.

After introducing similar legislation in 2020, Councilmember Kenyan McDuffie reintroduced a reparations bill, the Reparations Foundation Fund, and Task Force Establishment Act in 2023 with nine other council members’ support. The bill would create a fund and a nine-member task force to assess the district’s needs accurately and determine how reparations could be provided. The task force will study the institution of slavery, discrimination, and the lingering adverse effects of slavery on DC’s Black community. The task force will identify, compile, and synthesize the research and information gathered and then issue recommendations on educating the public on the findings and the types of reparations needed. Over 100 community members testified to the bill’s importance at the DC Council hearing in 2023. Since then, a group of cross-sector leaders that testified in support of the bill that supports reparations for Black people in DC have continued to meet monthly as the DC Reparations Coalition: members of the DC Reparation Coalition have periodically met with councilmember to offer recommendations to the DC Council to strengthen the pending legislation. The DC Fiscal Year 2025 budget passed in June 2024 allocated $1.5 million to pre-fund the implementation of the legislation, as introduced.

Reparations legislation was enacted, but other steps remain for implementation.

On December 17th, 2024, the Council of the District of Columbia voted unanimously for the Reparations bill, which was renamed the “Insurance Database Amendment Act.” However, the bill must still navigate the congressional review process.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

The Washington Post December 17 2024

iF, A Foundation for Radical Possibility September 2024

Safety Summitt: Prevention Over Punishment February 2022

Committee on the Judiciary for the District of Columbia June 2023

LUSH Cosmetics May 2024

National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy January 2024

State of California Department of Justice June 2023

Council Office on Racial Equity August 2023

Council Office on Racial Equity December 2024

Our Solutions

The U.S. Congress should take no action, and allow the Insurance Database Amendment Act to become law.

special thanks

DC Reparations Coalition ★ iF, a Foundation for Radical Possibility ★ First Repair ★ Dr. Tanya Golash-Boza