mandatory minimums

Mandatory minimums are extreme sentences that DC residents and victims want eliminated.

- 4 Minute Read

By imposing mandatory minimum sentences, courts lose the ability to customize sentences based on individual circumstances and victims’ stated goals and preferences. Mandatory minimum laws do not deter crime but pressure defendants into plea bargains. Many states, both Republican- and Democrat-led, have repealed such laws in the past 25 years. In DC, 1 in 5 sentences is mandatory, disproportionately affecting Black people. These laws do not always address the most critical issues; one such law on theft is noted as the nation’s harshest. Legal experts, DC stakeholders, and 7 out of 10 residents support ending mandatory minimums. DC should join neighboring states like Virginia and Maryland, in eliminating mandatory minimum sentences.

What you need to know

Mandatory minimums lead to extreme sentences.

When not bound by mandatory minimum sentences, courts are required to consider various factors in sentencing, including the victims’ perspective and case specifics. In DC, judges follow voluntary sentencing guidelines based on past sentences for similar cases to have rational and consistent sentencing practices. However, mandatory minimums remove this discretion, forcing judges to impose long sentences regardless of circumstances or community safety. This gives prosecutors leverage to coerce defendants into plea bargains, as refusing could mean facing the mandatory minimum.

DC’s “statutory minimums” are not a break and lead to incarceration.

Statutory minimums, a type of mandatory minimums, differ from strict mandatory sentencing. They allow judges to sentence defendants to a minimum term but suspend the sentence, placing them on probation. However, if probation terms are violated, even for minor reasons like missing an appointment, the minimum prison term can be enforced. While statutory minimums may seem lenient, success on probation often depends on factors like financial stability and access to resources like substance use treatment. This disparity can lead to different outcomes for individuals based on their socioeconomic status.

Mandatory minimums do not increase public safety, and victims and the public oppose their use.

Lengthy prison terms do not improve public safety, and studies confirm that mandatory minimums do not reduce recidivism. A survey of DC residents revealed that 77% are in favor of scrapping mandatory minimum sentences, with backing across all eight wards. Nationally, 72% of Americans are more likely to support a candidate who votes against mandatory minimums. Victims organizations in DC and nationwide also reject the use of these sentences.

Mandatory minimums are not necessarily targeting the most serious conduct.

Mandatory minimums were promoted to the public to target serious and violent offenses, but actually impact a wide spectrum of behaviors. In some cases, people engaged in more serious behaviors face lesser penalties than those impacted by a mandatory minimum. A mandatory sentence of one year must be imposed if someone steals $25 from a roommate after two prior convictions for similarly minor theft. The Criminal Code Revision Commission looked at this “theft-specific recidivist penalty” and found “the District’s current statute is the most severe in the nation”–no other state has a mandatory minimum for such an offense.

Mandatory minimums – even when applied to a homicide – can lead to unjust outcomes.

Someone convicted of First Degree Murder faces a 30-year mandatory minimum sentence. The threat of decades in prison incentivizes an innocent person to plead guilty to another crime, even if they did not commit the crime they were charged with. Here, where the stakes are highest, a judge cannot review the decision, and the risk that someone will be wrongfully convicted of a crime increases. Not every homicide is the same or should treated the same the way the mandatory minimum requires: The mandatory minimum for homicide has impacted people who have been abused, were victims of sex trafficking, or who euthanized a loved one navigating a serious, end-of-life illness. Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Montanna, New York, Virginia, Texas, and Utah have lower mandatory minimums than DC. Individuals facing mandatory minimums for homicide have had to launch fundraising efforts for legal defense and influence prosecutor charging practices when facts show the person shouldn’t have faced the extreme sentence. Under our homicide statutes, a getaway driver for a burglary would face a mandatory minimum for felony murder when someone is killed during the burglary, even without his knowledge.

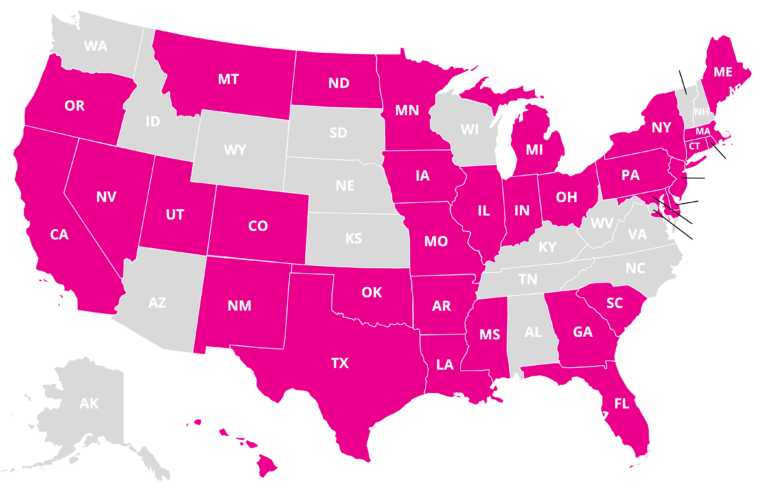

States With Mandatory Minimum Sentencing Reforms

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

American Law Institute April 2017

HIT Strategies Survey of DC Residents June 2022

Criminal Code Revision Commission March 2020

Kevin Ring, Former President, Families Against Mandatory Minimums. 2022

DC Sentencing Commission August 2021

American Bar Association August 2017

National Network for Victim Recovery of DC October 2022

Council Office of Racial Equity October 2022

Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice. September 2022

National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. 2018

special thanks

Jesse Brennan ★ Madison Meyer ★ Briana Scholar ★ Darby Hickey ★ Daniel Landsman

Last Updated on November 1, 2023.

Appendix

1. Victim groups oppose the use of mandatory minimums.

The National Network for Victim Recovery in DC has said, “Eliminating mandatory minimums protects victims’ rights.” A national survey of crime survivors’ perspectives found, victims are more than three and a half times more likely to prefer authorizing earned credits toward sentence reductions for people who participate in rehabilitation, treatment, education, and job training programs and follow prison rules (73% to 20%) to requiring completion of the full sentence lengths issued at sentencing, regardless of whether they participate in rehabilitation.

2. Two-thirds of the states have eliminated some mandatory minimums.

In response to research on the consequences of mandatory minimums, according to Families Against Mandatory Minimums, over the past twenty-five years, 33 states (including states under Republican and Democratic leadership) have passed at least 75 pieces of legislation to repeal some mandatory minimum sentences. The Virginia State Crime Commission recommended in 2020 to “endorse legislation to eliminate all mandatory minimum sentences with a term of confinement from the Code of Virginia,” the state’s last Governor said he would not sign another mandatory minimum sentence into law. In 2016, Maryland’s Democratic legislature and Republican Governor repealed all mandatory minimums for drug sentences.

3. Black people account for 9 out of 10 people sentenced under mandatory minimums.

Surveys of young people show that people White, Black, and Latinx young people are just as likely to report having carried a weapon or had access to a loaded gun. When the DC’s Criminal Code Revision Commission reviewed all felony sentences imposed from 2009 to 2018, among the three types of weapons offenses that most often resulted in a mandatory minimum sentence, 95 percent or more of the individuals who were charged and convicted were Black. Ninety-seven percent of those charged with carjacking offenses that carry a mandatory minimum were Black. Research on federal cases has shown that prosecutors bring mandatory minimums 65 percent more often against Black defendants.

4. Legal experts say we should eliminate mandatory minimums and revise these laws.

The American Law Institute—joined by two Presidential crime commissions, the American Bar Association, and the Federal Judicial Conference–recommended that no mandatory minimum prison sentence be enacted for any offense. The prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, and other experts who contributed to the Criminal Code Reform Commission studies led the group to recommend that “sentencing guidelines, rather than statutory mandates, are a more appropriate way to guide judicial decision making among competing sentencing mandates.”

5. Many mandatory minimum charging decisions are resolved through pleas.

The DC Sentencing Commission looked at felony sentences imposed by the Superior Court from 2015 to 2020 and found that mandatory minimums were one in five sentences imposed and that mandatory minimums are twice as likely (94 percent) to result in a prison sentence than other convictions (44 percent). The largest number of people sentenced for a mandatory minimum (39 percent) was for the charge of Unlawful Possession of a Firearm by a Person with a Prior Felony Conviction (FIP); nearly 90 percent of these cases were the result of a plea agreement, and these convictions almost always resulted in a prison sentence (96 percent) with an average sentence of two years.

6. What are examples of statutory minimums, and how do they work?

The DC Sentencing Commission gives an example of an offense with a three-year statutory minimum where the judge can sentence the defendant to three years but can suspend the entire sentence and place the defendant on probation. First and second-degree burglary are two crimes with statutory minimums where the judge can suspend part of the sentence. If someone does not succeed in the community, the full prison term can be imposed – up to five years for the first-degree and two years for second-degree burglary.

7. Mandatory minimums do not increase safety.

The National Institute of Justice says that “increasing the severity of punishment does little to deter crime. Laws and policies designed to deter crime by focusing mainly on increasing the severity of punishment are ineffective partly because [the individuals] know little about the sanctions for specific crimes.” A review of 29 studies of firearms crimes that impose mandatory minimums said there was “little empirical support” that mandatory minimums increase safety. The Pennsylvania Sentencing Commission looked at mandatory minimums and said, “[N]either length of sentence nor the imposition of a mandatory minimum sentence alone was related to recidivism.”

8. More serious behaviors face lesser penalties than those covered by a mandatory minimum.

The Sentencing Commission has shown than, in DC, six out of ten mandatory minimum sentences imposed are for weapons offenses, 23 percent are for violent offenses, with some mandatory minimums applied to Driving Under the Influence – generally a nonviolent misdemeanor offense. A person convicted of unarmed carjacking where one was hurt faces a seven-year mandatory minimum, while a person who seriously injures a victim with a beating faces a maximum sentence of ten years under aggravated assault. A mandatory sentence of one year must be imposed if someone steals $25 from a roommate after two prior convictions for similarly minor theft. A pickpocket could face a mandatory minimum for having a gun in her sock that she did not use and did not intend to use during the crime.