Halfway houses

Halfway houses were supposed to help people prepare for a future in the community, but their residents say they felt like they were still in prison.

- 9 Minute Read

Government entities that fund halfway houses and the non-profit agencies that run them say that these facilities allow people to leave during the day to work, access treatment and medical services, and rebuild community ties. But research on the outcomes of people who finish their sentence in a halfway house shows they do not reduce recidivism, and large facilities, like 300-bed facilities used in DC, have a poor track record of rehabilitation. Oversight entities and former residents of halfway houses say they are overcrowded and too far from worksites. Residents also experience barriers that limit their access to medical care and treatment and are subject to rules that are arbitrary, excessive, and hard to challenge. Efforts to build a new halfway house in DC have been impacted by community opposition and the current plans would result in a large facility, like the one that had to be closed due to unsafe accommodations and inadequate re-entry services. If an individual needs to finish their sentence in a halfway house, they should be in an environment that is less crowded and community-centered, with programming, rules, and structures that are focused on rehabilitation, not punishment.

What you need to know

Halfway houses are supposed to ease someone’s transition from prison to the community.

Individuals sentenced to prison may be offered the opportunity to serve out the last few months of their sentence in a halfway house. Halfway houses are generally places where one is authorized to leave during the day to work or seek other services, but must return at the end of the day. DC residents and people convicted of DC code offenses may finish the prison term with the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) in halfway houses that are called “residential reentry centers” (RRCs). The BOP states that halfway houses “provide a safe, structured, supervised environment, as well as employment counseling, job placement, financial management assistance, and other programs and services.” The Second Chance Act of 2008 expanded the use of halfway houses, allowing individuals to serve up to twelve months of their sentence in these facilities. The federal government currently contracts with private corporations and nonprofit organizations to operate 159 RRCs nationwide. The BOP is not required to place an individual in a halfway house, and a person can refuse placement in a halfway house and finish their full sentence in prison.

With reports of unsafe conditions and a lack of services, the last halfway house in DC closed in 2020.

Until 2006, nine halfway houses were located in DC to house District residents. Reports from the Corrections Information Council and advocates showed that these facilities faced challenges in providing employment programming, transportation, and transparent grievance procedures. By 2020, Hope Village was the only halfway house for DC men, who make up most of the District’s incarcerated population. As the largest federally contracted halfway house in the country, Hope Village had a capacity to house 304 people. There were calls for Hope Village’s closure over unsafe accommodations and inadequate re-entry services. When two residents filed a class-action lawsuit alleging that the facility failed to take even the most basic measures to protect them from the COVID-19 virus, Hope Village closed soon after in April 2020. Since then, DC has lacked a halfway house for men returning from prison.

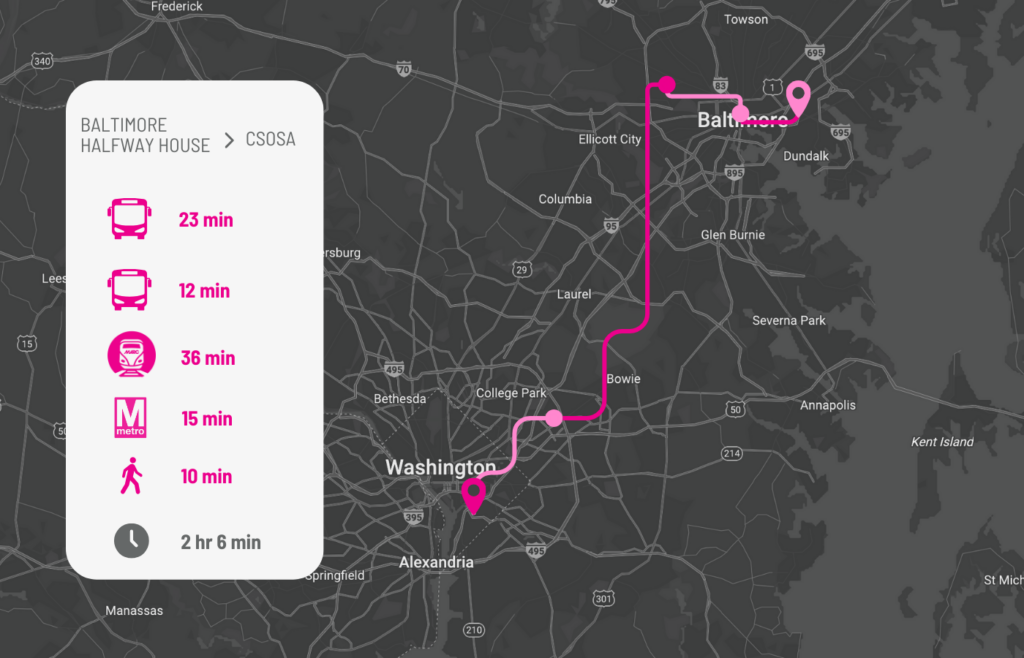

Most DC residents who return to the community through halfway houses are in Baltimore.

Twelve hundred people were released from a BOP facility in 2023 who were convicted of DC code offenses. The BOP and the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council do not currently publish data that details, by location which halfway houses DC residents are assigned to. Under the First Step Act, the BOP may designate someone to “a facility as close as practicable to the prisoner’s primary residence and, to the extent practicable, in a facility within 500 driving miles of that residence.” The Office on Reentry and Citizen Affairs (ORCA) told the Council of the District of Columbia Committee on Housing in May 2024 that, “most men [returning from prison to halfway house] are being sent to Baltimore upon release, at the Volunteers of America Chesapeake facility.” The Corrections Information Council (CIC) reported in January 2025 that the Baltimore halfway house had 58 people convicted of DC code offenses as of May 2024. Of those residents, 96 percent were Black returning citizens. The average length of time someone resides in this facility varies between 30 days and 1 year, and 20 to 25 new residents arrive each week.

The conditions people experience in the halfway house undermine the factors that reduce recidivism.

After meeting with residents in Baltimore, the CIC said “the facility is overcrowded.” The personal experiences of people who spent time in the Baltimore halfway house suggest that the conditions there make it harder for individuals to connect to the types of employment, treatment, and education programs, and procedural fairness around the rules that will help someone succeed in re-entry. Some people have chosen to finish their full prison term rather than go to the Baltimore halfway house.

Employment

Treatment

Education

Procedural Fairness

Some people have chosen to finish their full prison term rather than go to the Baltimore halfway house.

Plans to build a new halfway house in DC have been delayed six years.

Efforts to build a new halfway house began prior to the closing of Hope Village. CORE DC, a local nonprofit, was awarded a $60 million contract in November 2018 to build a new 300-bed halfway house for men, but significant community opposition to siting the building in Ward 5 and, later, Ward 7 dramatically slowed the process. When the process slowed even further in 2021 due to an emergency resolution that would have transitioned the site into an urban park, the DC Reentry Action Network (RAN) said, “the facility’s placement in Ward 7 is imperative because this is home or near home for many of the individuals returning. The opportunity to come home and be supported in their community is a necessary element for returning citizens to create new lives and to exercise their self-determination.” Officially, very little has been said about the delays in opening since then. In February 2024, the Department of Corrections said, “DOC has yet to explore an alternate model to halfway house placement for men in DOC’s custody.” As of May, 2024, the Committee on Housing asked ORCA to “provide clear updates regarding the construction of the halfway house to the committee and the public. Public updates could be on the agency’s website or social media.” As of February 2025, pictures of the site of the new halfway house do not show it is ready to accept residents. CORE DC’s representative in DC has not offered a date when the halfway house would open.

Photos by Terrell Peters

Reentry organizations and leaders have a vision for how the halfway house could be geared toward rehabilitation.

Since 2019, a group of individuals who actively support an expansion of reentry services in DC have been working with CORE DC to expand the types of services that could be provided at the new facility. A CORE DC Electronic Monitoring Community Relations Board is working “as a liaison and central conduit for communication and mutual support between [CORE DC] and its neighbors” and to “enhance the work of the program staff, and enrich the lives of its residents, in the service of fostering a reentry experience for those residents that prepares them for life in the community and minimizes the changes for future recidivism.” It was envisioned that this entity would help provide increased access between community-based organizations that serve people coming out of prisons and jails and the residents of the halfway house. As of June 2023, the District Task Force on Jails & Justice reported that CORE DC had not “negotiated Memorandums of Understanding (MOU) with community-based organizations, supporting access to resources and support for its halfway house residents while in the new facility and on-home confinement.”

Large facilities, like halfway houses, do not have a great track record in reducing recidivism.

One challenge CORE DC will have to overcome is that the research on large “congregate care” facilities, like halfway houses, has not shown that they reduce recidivism or maintain safe environments. In general, research does not show positive public safety outcomes from halfway houses. In Pennsylvania, the outcomes of those who went straight back to the community from prison and those who finished their sentence in a halfway house were compared, and “the [people] who spent time in these facilities were more likely to return to crime than [people] who were released directly to the street.” The Pennsylvania Correction Secretary referred to their halfway house system as “an abject failure.”

Smaller, more homelike, treatment-rich environments are more likely to reduce recidivism.

While there is not much field research on specific types of halfway house environments that would have better public safety outcomes, there is literature around European correctional models that point towards a more successful post-prison support system. In Norway and Finland, facilities more closely resemble home than incarceration facilities, and residents have freedom to work, seek education, and come and go from their placement. These facilities have better rehabilitation and recidivism outcomes than those seen in American corrections systems. Currently, European models are being adopted in Connecticut and Pennsylvania. Studies show that people who receive specialized case management services that help individuals connect to treatment, programs, and other supports see shorter lengths of stay in halfway houses and are less likely to return to prison.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

More than our Crimes September 2024

District of Columbia Corrections Information Council January 2025

Families Against Mandatory Minimums April 2024

DC Justice Lab February 2025

Our Solutions

DC should build on recommendations from returning citizens and lessons learned from elsewhere, and:

- Ensure places where people can complete their sentences are smaller, with fewer residents and more home-like designs

- Implement programming, rules, and structures in halfway houses that are focused on rehabilitation, not punishment

- Require mental health professionals to be on-site in halfway houses

- Eliminate obstacles that prevent residents from working

special thanks

Pamela Bailey ★ Ronnell Brown ★ Darnell Keys ★ Kenard Johnson ★ Earl Kenny