Parole and Supervised Release

Even the United States Parole Commission doesn’t want to be the body deciding whether to deny parole to people convicted of DC Code offenses or send people back to jail.

- 13 Minute Read

More than twenty years ago, DC shifted from a parole system, where one might complete some portion of their prison sentence in the community, to a system where many people serve at least 85 percent of their sentence and then serves an additional period of mandatory supervised release. Now, the United States Parole Commission (USPC), – a federal agency– decides whether or not all people released from prison can remain in the community or be revoked and sent back to prison or jail, and for the few people still eligible, decides who can be paroled. It also decides whether to end the terms of supervision early. Many stakeholders, including the USPC want someone else to make these fundamental decisions over the life and liberty of DC residents, but DC has missed a critical opportunity to work with the U.S. Congress to change how the system works. There are different points of view on what should happen next: some think we should end parole altogether and focus on broader sentencing changes that would shorten prison and supervision terms, while others think the role of the USPC could shift to either judges or a DC-run parole board.

What you need to know

Fifteen thousand DC residents are under supervision.

15,000 DC residents are under some form of community supervision. This includes 8,300 defendants not yet convicted of a crime under pretrial supervision. There are 4,200 people who were sentenced by the courts to a jail sentence, and some or all of their sentence is suspended, and they are placed on probation. There are also 1,800 people on post-prison supervision after being incarcerated in the Federal Bureau of Prisons. The Federal Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency and the Pretrial Supervision Agency are responsible for the day-to-day monitoring of these individuals: they review whether someone complies with conditions, like getting and keeping a job, completing treatment, and paying court-ordered fines and fees. If someone does not comply with these conditions, CSOSA and PSA may request a revocation hearing, which could result in that individual’s supervision being revoked and incarceration in a prison or jail as a sanction.

There are two forms of post-prison supervision in DC: supervised release and parole.

After someone serves a prison sentence, that person can be on parole or supervised release. The 507 people currently on parole supervision received an indeterminate sentence. An indeterminate sentence is a type of custodial sentence that consists of a range of years (such as five to ten years) and not a fixed time, which means the convicted person’s release date is left open. The 1,351 people on supervised release received a determinate sentence which means they must serve their entire sentence incarcerated absent some good-time credits, and then will serve an additional post-prison time under supervision.

Difference between parole and supervised release

The George Washington University Law School Parole Practice Manual for the District of Columbia gives the following examples of indeterminate and determinate sentences, as it relates to the differences between parole and supervised release.

Indeterminate Sentence and Parole

Mr. Johnson is convicted of a homicide offense. The judge sentences Mr. Johnson to a prison term of twenty years to life. At twenty years, Mr. Johnson is eligible for parole but can serve more time if USPC determines that he should not be released on parole. If released on parole at any time after twenty years, Mr. Johnson remains on parole until the maximum term of his sentence, which in this case is the rest of his life.

Determinate Sentence and Supervised Release

Mr. Johnson is convicted of a homicide offense. The judge sentences Mr. Johnson to thirty-five years in prison and five years of supervised release. Mr. Johnson must serve all thirty-five years of his sentence in prison, with certain reductions for good time credits. After serving thirty-five years in prison, Mr. Johnson is on supervised release in the community for five years.

Indeterminate Sentence and Parole

Mr. Johnson is convicted of a homicide offense. The judge sentences Mr. Johnson to a prison term of twenty years to life. At twenty years, Mr. Johnson is eligible for parole but can serve more time if USPC determines that he should not be released on parole. If released on parole at any time after twenty years, Mr. Johnson remains on parole until the maximum term of his sentence, which in this case is the rest of his life.

Determinate Sentence and Supervised Release

Mr. Johnson is convicted of a homicide offense. The judge sentences Mr. Johnson to thirty-five years in prison and five years of supervised release. Mr. Johnson must serve all thirty-five years of his sentence in prison, with certain reductions for good time credits. After serving thirty-five years in prison, Mr. Johnson is on supervised release in the community for five years.

DC replaced parole with supervised release, and decisions shifted to the United States Parole Commission.

Since the 1930s, there had been a DC Board of Parole that made decisions about whether an individual could serve some of their indeterminate sentence in the community. Starting in the 1980s and continuing for three decades, sixteen states and the federal government abolished parole. DC followed this shift at the millennium: Anyone sentenced before August 2000 remained eligible for parole under the old laws and rules that applied before the change, but everyone serves under a determinate sentencing system going forward after August 2000. At the same time as the sentencing structure was changing, the US Parole Commission assumed a new role for people in DC convicted of crimes: First, they assumed the authority to decide when to hear the case of and release someone who is parole-eligible; second, whether to revoke someone on parole or supervised release and decide how much time they should serve and third, whether to terminate parole or supervised release early. As of 2021, there were still 661 people who were incarcerated in the Federal Bureau of Prisons eligible for parole because they were sentenced in the 1990s.

Parole boards have been criticized for how they make decisions and the outcomes they produce.

Prison Policy Initiative has summarized the main criticisms of parole boards and why they are ineffective: most do not allow face-to-face meetings between members and people seeking parole to discuss their case; how they make decisions is not clear or transparent, making it difficult for people seeking parole to know why they were denied release, and the boards do not provide adequate assistance or training to individuals seeking parole to prepare for the interview. Most importantly, parole boards have been criticized for focusing on the nature of the individual’s original offense from decades ago rather than on objective factors, like decades of positive behavior in prison or family ties that show that a person could be released without any adverse effect on public safety. Nationwide, the number of people released from prison based on a decision by a parole board declined from 70 percent in the 1970s to less than 20 percent today.

In DC, parole boards have been called “harsh” and too focused on revoking people to jail.

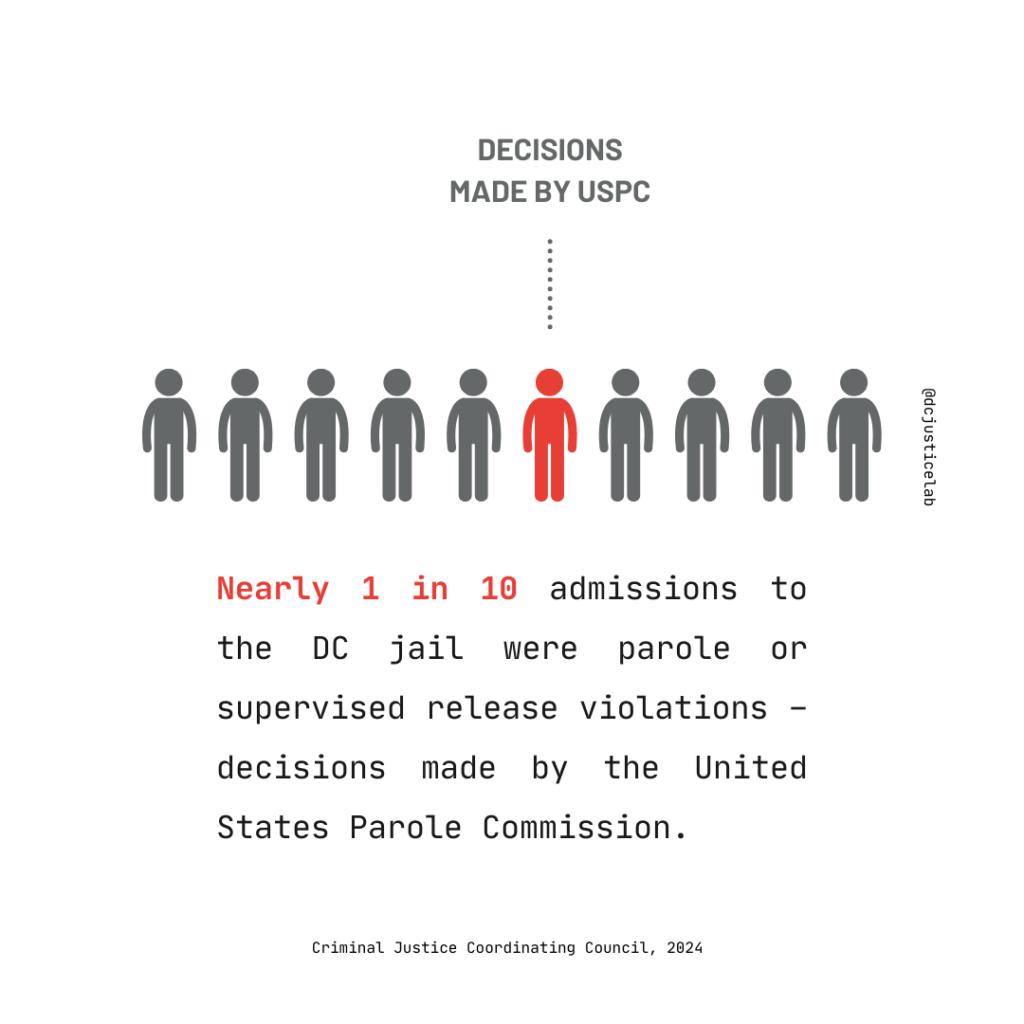

The two parole boards that have operated in DC have been criticized for the same reasons as parole boards around the country. USPC has been described as having “unnecessarily harsh practices” that undermine the original sentencing judges’ decision by using criteria around release decisions that are too focused on the severity of the offense from decades ago, relying less on whether the person has completed rehabilitative programs in prison and can be safely released. The Public Defender Service said they have seen USPC revoke individuals back to prison or jail for minor behaviors that included fair evasion, marijuana use, and whether they had been successful in mental health treatment. Today, about 9 percent of admissions to the DC jail were parole or supervised release violations.

Individuals eligible for parole in DC faced confusing processes and were denied release.

At hearings and in news media covering this issue, people who had been eligible for release explained some of the challenges they have had with the current system. One individual said they met all the rehabilitative benchmarks of the prison system but was denied release six times at six different parole decision hearings. Another individual said that despite spending four months in jail on a charge that was dismissed by a judge, the USPC decided that one positive drug test was enough of a reason to revoke and reincarcerate the individual for a year in the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Another individual with a spotless record said he could not get USPC to provide him the information to terminate his parole, and after working with an attorney, the lawyer received an email that showed USPC had produced a certificate noting he completed parole, but would not email this document to him or his CSOSA officer so that a termination process could be completed. Another individual spent 29 years in prison without a disciplinary infraction, completed every program they could enroll in, taught classes for others incarcerated, and mentored those younger than him, and was still refused parole three times.

All DC residents experience the consequences of a failing parole and supervision system.

People seeking parole are in Federal Bureau of Prisons facilities that may be hundreds of miles from their homes, making it harder to maintain community ties. Denial of parole means this person still experiences distance from their families, community resources, and support systems that are needed to steer clear of crime in the future. Individuals denied parole have said there is a profound psychological impact of believing they may earn their release and still not be able to go home. When the USPC makes decisions about whether to revoke an individual’s supervision, it can lead to jail overcrowding and dangerous institutional conditions. In addition, DC residents pay for the cost of reincarcerating that individual in the DC jail and Federal Bureau of Prisons. The lack of transparency around how the rules of release work undermines a community’s collective sense that the justice system can act fairly.

There are different visions for how to replace DC’s current parole system.

DC Could:

Establish a locally run Board of Parole: One perspective is that DC should return to running its own parole board that could make the types of decisions currently being made by the USPC. One critique of this perspective is that since 72 percent of parole boards were graded an F for their processes and are not able to operate efficiently, fairly, or effectively, why recreate this system with the DC Board of Parole?

Judges make parole and revocation decisions: One approach would be to see people return to their sentencing judge for the three decisions the USPC currently makes governing DC residents. One concern about this approach is that the courts have not shown a willingness to take on this additional work and its associated costs.

Abolish parole, but keep the focus on sentencing reforms: Former DC Council member Mary M. Cheh (D-Ward 3) commented that re-creating a local parole board “doesn’t serve any good purpose” and instead encouraged continuing the types of reforms that would end mandatory minimums and determinate sentencing, and end supervision when it no longer has a public safety benefit. DC could also expand Second Look reviews to a broader group of individuals. One concern about this approach is that the U.S. Congress has not allowed these types of sentencing changes to move forward.

DC missed the opportunity to change its parole and supervised release system.

The U.S. Congress never intended a permanent role for the USPC in DC’s justice system: it could be sunset by an act of Congress, including by not funding the commission. USPC said they were ready to end the arrangement in 2019. In 2021, the Mayor of the District of Columbia hired a consultant group to map out what a new system or approach for DC could be. These efforts failed to materialize a concrete plan by the end of 2022. With the election of a Congress that has actively blocked DC criminal justice reforms, some say changes to the parole system are “dead in our current political climate.” In 2023, DC Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton introduced legislation to require federal officials in charge of supervision agencies have to live in DC, but this legislation was not enacted. Bipartisan legislation in the Senate was introduced in 2024 that sought to end supervised release for all people in the Federal Bureau of Prisons, including DC residents.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

Committee on the Judiciary and Public Safety May 2021

Robert Davis – Policy Academy Proposal February 2024

The Washington Post October 2022

Rethink Justice and the DC Reentry Task Force April 2021

Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia October 2022

Justice Policy Institute December 2019

Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights & Urban Affairs March 2018

DCist July 2022

Our Solutions

DC and the US Congress should:

The USPC should:

- Presume anyone they review should be paroled

- Be transparent and clear about how someone can achieve a positive release decision

- Base decisions around whether someone has been rehabilitated and changed their lives

- Ensure that releases are tied to reentry plans

- Cease imposing prison sentences for administrative violations of supervision and for arrests that do not result in a conviction

- Proactively terminate people from supervision after 6 months to a year in the community

- Increase accountability and oversight of its decisions to the communities impacted.

special thanks

Robert Davis ★ Rashida Edmonson-Perry