sex registries

Registries increase homelessness and joblessness and don’t increase safety.

- 4 Minute Read

Registration and notification laws for people convicted of sex offenses cause significant harm without providing any real public safety benefits. The scientific consensus that has emerged over the past quarter century shows that registries do not lead to safer communities and instead create barriers to housing, employment, and education that make us all less safe. Research finds Black men are forced to register at much higher rates than any other group. While DC’s registration and notification laws are not as punitive as other jurisdictions, there is no evidence to continue using them. DC should create legislation to become the first jurisdiction to adopt the American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code recommendations to eliminate the most harmful aspects of these laws and the policies and practices that flow from them.

What you need to know

Registration and notification laws are punishments that continue after a sentence ends.

A registry is a system for monitoring and tracking people convicted of sex offenses in the community. After someone “registers” with a state or jurisdiction, that information is published publicly on a website, including details like their name, home and work addresses, and information on their past convictions. While the 2006 Adam Walsh Child Protection & Safety Act (AWA) was intended to incentivize states to create a registry and conform with the minimum federally imposed standards, only 18 states are “substantially compliant” with AWA, and no two states use the same system. Each state and jurisdiction in the US has its own registry and implements how that information is collected, maintained, and shared. In December 2018, when the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children published its last count, there were more than 900,000 people on registries in the US.

Registries label someone a “criminal for life” and disproportionately impact Black and LGBTQIA+ people.

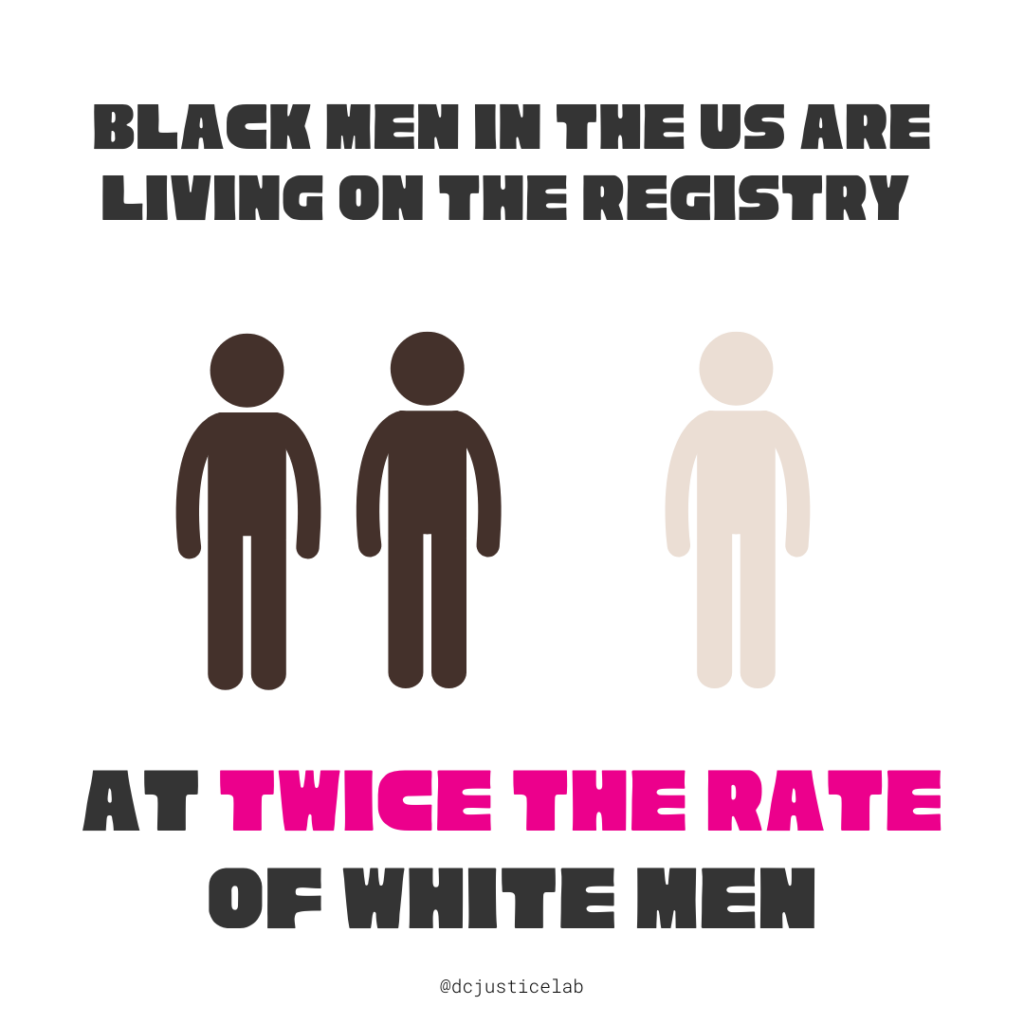

Registration and notification laws entrench a permanent negative identity on someone — it implies that someone is currently engaging in illegal behavior when the vast majority of people convicted of sex offenses do not commit another crime. It is based on a historical crime of conviction, which does not represent who that person is today. Registries are an extreme and harmful example of criminal record discrimination and the need for sealing and expungement. Studies show that registries disproportionately impact the LGBTQIA+ community, including young people and adults. Black men are placed on registries at twice the rate of white men, with one out of every 119 Black men on the registry — about one 1 percent of the Black adult male population. People on registries have experienced discrimination, harassment, and vigilantism.

Registries do not increase public safety, but they do add additional barriers to reentry.

Research shows that registration and notification laws do not create safer communities. Registries do not reduce the rate of sexual violence or the rate of recidivism and do not deter someone from committing a sex offense. Nine out of ten people convicted of a sex offense will never commit a new sex-related crime. However, when considering the circumstances of people who do commit another crime, studies have shown that registration and notification laws increase recidivism because they can foster a sense of hopelessness and reduce the incentive to avoid crime. The barriers someone with past convictions faces around housing, employment, and education are magnified by the registry. Persons forced to register for life are even banned from federal public housing assistance.

Registries do not protect children.

Registries have been promoted as a way to protect children from sexual abuse. Research shows that ninety-five percent of sex-related offenses are committed by someone who has no prior history of such a crime, so they would not be on any registry. Ninety-three percent of child sexual abuse is committed by someone known by the child — not a stranger. In this way, the registry misdirects the public by focusing concern on people living with prior convictions, which is not an accurate indication of present or future crimes.

In DC, a federal agency enforces the registry, while the police direct public notifications.

The Federal Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA) maintains the sex offender registry for DC. The Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) is authorized to notify the public about who is on the registry. The split in function, as described by the MPD, means they won’t guarantee the accuracy of the information they provide to the public. Registration is based on the offense, not based on an individual assessment that someone may be more likely than another person to engage in a sex offense. A court cannot remove a person from the registry. Research shows failing to register is not a significant predictor of sexual recidivism, raising serious questions about the societal benefits of such prosecution.

In DC, a registry can extend your punishment for decades.

DC law requires lifetime registration for some offenses. For most crimes, a person must remain on the registry for ten years after their sentence ends. For example, after being sentenced for an offense at age 25 and serving a 10-year prison sentence, you would remain on the registry for an additional 10 years. That equals 20 years of punishment in total. A person might have to register even if their offense occurred decades ago and they have lived a crime-free life ever since. While the consequences of failing to register are significant, research shows that most registry violations are minor and that the person on the registry is easily located.

DC’s registry includes people’s names and general addresses on public websites.

Open Data DC maintains a website that lists 1,300 individuals’ records on the DC registry. The information published may include whether they live, work, or attend school at that location. An analysis of the website data shows 115 people on the DC registry are in their seventies and 14 more people over the age of 80. DC publicly displays information about a man who is 98 years old.

DC has not implemented more restrictive laws, policies and practices used elsewhere.

In addition to implementing federal laws around registration and notifying the public, at least 30 states have residency restriction laws that prevent someone on the registry from living or working close to a school and or park. This can contribute to financial and emotional instability, increasing the likelihood of homelessness and unemployment. Residency restrictions are additional state and jurisdictional laws and are not required under federal law (and the U.S. Justice Department opposes their use). DC Council has never even considered creating residency restrictions in DC, allowing people forced to register to return to their communities where they have the greatest social support and chance of a successful reentry.

DC should invest instead in evidence-based primary prevention and victim services.

Primary prevention is a public health model that focuses on the causes of sexual violence and seeks to prevent crime before it occurs. Education can disrupt harmful sexual behavior before it occurs. People who have experienced sexual violence support alternatives to extreme sentencing, like investment in primary prevention and services.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

State University of New York (Albany) May 2016

U.S. Department of Justice 2016

September 2015 The New York Times – Editorial

Prison Policy Initiative – reporting on U.S. Justice Department data June 2019

International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 2015

Our Solutions

DC Should:

- Adopt the American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code recommendations to eliminate public notification and shrink the size of the registry

- Educate the public on the causes of sexual crimes against children

- Study and evaluate how current laws and practice work

- Stop displaying work and employment information on the registry

- Ban CSOSA from asking people for additional information they are not mandated by the DC Code to collect

- Move the registry away from a federal agency to a DC agency

- Create a legal pathway off the registry for everyone

Contact us about this topic

special thanks

Galen Baughman ★ Roger Lancaster ★ William Dobbs ★ Catherine Hanssens ★ Lenore Skenazy