Solitary confinement

The US Senate Judiciary Committee held hearings on solitary confinement – DC’s Judiciary and Public Safety Committee has not.

- 8 Minute Read

When someone incarcerated is placed in solitary confinement, they are kept alone in a prison or jail cell with no meaningful human interaction and have their mobility restricted in a limited physical space. Research shows that people who experience solitary confinement while incarcerated are more likely to die, experience deteriorating mental health, and engage in suicidal behavior. Solitary confinement can make prisons or jails less safe. Solitary confinement can increase recidivism upon release. Prisons and jails across the country, from Washington State and New Jersey to San Francisco and New York City are working to reduce the use of solitary confinement. Even corrections officers see the problems caused by solitary confinement and are developing alternatives to its use. While DC does not regularly report this, information from oversight hearings, the media, and ex-staff from the jail report that solitary confinement is being used. People who have personally experienced solitary confinement or its aftermath want it eliminated. The Council of the District of Columbia should follow the example set by the United States Senate by holding a hearing on solitary confinement. Then, the Council should pass legislation sponsored by seven Councilmembers to end the practice.

When someone incarcerated is placed in solitary confinement, they are kept alone in a prison or jail cell with no meaningful human interaction and have their mobility restricted in a limited physical space. Research shows that people who experience solitary confinement while incarcerated are more likely to die, experience deteriorating mental health, and engage in suicidal behavior. Solitary confinement can make prisons or jails less safe. Solitary confinement can increase recidivism upon release. Prisons and jails across the country, from Washington State and New Jersey to San Francisco and New York City are working to reduce the use of solitary confinement. Even corrections officers see the problems caused by solitary confinement and are developing alternatives to its use. While DC does not regularly report this, information from oversight hearings, the media, and ex-staff from the jail report that solitary confinement is being used. People who have personally experienced solitary confinement or its aftermath want it eliminated. The Council of the District of Columbia should follow the example set by the United States Senate by holding a hearing on solitary confinement. Then, the Council should pass legislation sponsored by seven Councilmembers to end the practice.

What you need to know

- What is solitary confinement?

Solitary confinement means 22 hours or more a day in a cell without meaningful human contact.

While there is no agreed-upon definition in the United States, according to the United Nations, solitary confinement is the confinement of someone to a cell for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact. Prolonged solitary confinement is the same experience in excess of 15 consecutive days. Corrections systems have placed people in solitary confinement for disciplinary reasons, because someone may be at risk for violence from other residents, because the courts ordered it, or because they think an individual may engage in self-harm. It has been portrayed that solitary confinement is reserved for people who have been convicted of violent crimes or who engage in violence in institutions, but it has been reported that people have been placed in solitary confinement for nonviolent disciplinary reasons, such as talking back to a correctional officer. On any given day, 122,000 people in prisons and jails in the United States are estimated to be experiencing solitary confinement.

- How does solitary confinement impact people in jails, and safety?

Solitary confinement can negatively impact someone's health and mental health.

Research conducted over the last two decades shows that solitary confinement is not neutral, and people who have been placed in solitary confinement have had these negative experiences:

- Mental health: the isolating conditions of solitary confinement have been shown to exacerbate mental health challenges: Research looking at people placed in solitary confinement in a supermax prison found over thirty-three percent of people experienced psychosis and/or became acutely suicidal within the first fifteen days of confinement.

- Self-harm: A study on the New York City jail system found that individuals placed in solitary confinement were 6.9 times more likely to commit acts of self-harm and 6.3 times more likely to commit acts of potentially fatal self-harm than people in the general population.

- Mortality: Compared to people in the general incarcerated population one study found that people placed in solitary confinement were more likely to die after release, especially from suicide and homicide.

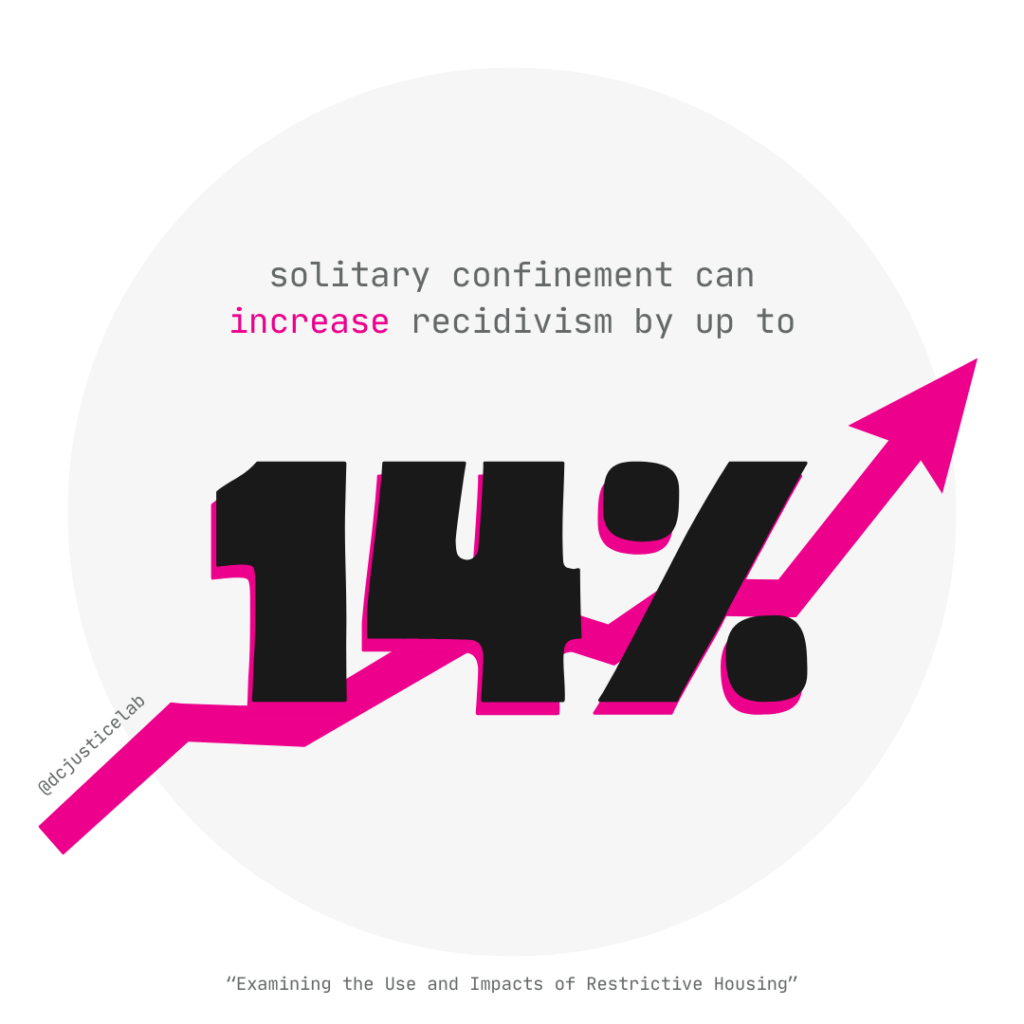

Solitary confinement can increase recidivism and may not make institutions any safer.

Research on the use of solitary confinement in an Ohio prison funded by the US Justice Department found short-term solitary confinement led to a 7 percent increase in the likelihood of recidivism and extended solitary confinement led to a 14 percent increase in the likelihood of recidivism. One federally funded study looking at prisons where DC residents may be incarcerated found “that neither the experience of [solitary confinement], nor the number of days spent in [solitary confinement], had any effect on the prevalence or incidence of the finding of guilt for subsequent violent, nonviolent, or drug misconduct.” The head of the National Institute of Justice has written, “the consensus across National Institute of Justice (NIJ) sponsored research on restrictive housing concludes that it is not an effective deterrent [for institutional violence].”

save & share ⤴

- Who wants to reduce the use of solitary confinement?

Corrections officials have called for an end to the use of solitary confinement.

The Association of State Correctional Administrators has said since 2015: “prolonged isolation of individuals in jails and prisons is a grave problem in the United States,” and the organization representing prison administrators committed to “ongoing efforts to limit or end extended isolation.” The Federal Bureau of Prisons (FBOP), where residents from DC may be incarcerated, is taking steps to end solitary confinement through changes to restrictive housing, but those efforts have yet to be fully implemented. The Director of the FBOP wrote she is

“keenly aware of how restrictive housing may harm a person’s mental, emotional, and physical well-being.” Unlike Washington, DC’s Department of Corrections, the Washington State Department of Corrections publicly publishes a plan that proudly proclaims that it is “tak[ing] the next step[s] towards reducing the use of solitary confinement.” Corrections officers and supervisors working in a prison in a southern state reported that the stress of managing individuals in these settings spilled over into their everyday lives, that staffing changes could help manage more people in the general population, and the lack of programming in solitary confinement is one reason, people do not come out better after the experience.

Federal, state and local lawmakers are working to eliminate solitary confinement.

Lawmakers at the national, state, and local levels have taken significant steps to eliminate the use of solitary confinement. New York State, New York City, and New Jersey had deliberative processes where lawmakers heard directly from individuals impacted by solitary confinement in their prisons and jails, and all three states passed legislation to restrict it. New York City’s ban on the use of solitary confinement in their jails was opposed by their mayor but may be implemented if there is a change in the executive. In all, 500 bills in 44 states have been introduced between 2018 and 2023 to address the issue of solitary confinement. In 2024, the United States Senate held public hearings and introduced legislation to eliminate the use of solitary confinement in the federal prison system where DC residents are incarcerated.

States and cities are pioneering alternatives to solitary confinement.

Different jurisdictions, including San Francisco, New York City, and New York State have programs that serve as alternatives to the types of issues that corrections officials say lead them to use solitary confinement. These programs focus on increasing out-of-cell group programming, responding to infractions with therapeutic approaches rather than punitive ones or isolation, and providing incentives to increase compliance with institutional rules. North Dakota and Washington state have reduced solitary confinement as part of system-wide corrections changes: these changes include expanding access to programming for people in prison, targeting programming to those at risk of placement in solitary confinement, and expanding more opportunities for out-of-cell time. System-wide changes in corrections systems that reduce solitary confinement also enhanced mental health screenings and positive behavior-based interventions and used alternative treatment units with enhanced out-of-cell time.

DC voters want to end the use of solitary confinement.

An ACLU of DC poll of 2024 voters found that fifty-five percent of DC voters opposed the use of solitary confinement at the DC Jail. More voters opposed solitary confinement than supported it in all eight wards. Support for ending solitary confinement increased to 62 percent when voters heard that “[t]he practice typically means placing a person in a very small, isolated cell for 22 to 24 hours per day.” After hearing, “research shows that solitary confinement does nothing to rehabilitate people and exacerbates or creates mental illness,” opposition to solitary confinement rose to 70 percent.

DC residents who experienced solitary confinement want to end its use.

Individuals in DC who personally experienced being in solitary confinement in a prison or jail or whose family members were in solitary confinement say it harmed them and the people in their community.

People's experiences with solitary confinement

- What can DC do to reduce solitary confinement?

DC must report on the use of solitary confinement at the jail more consistently and publicly.

The Director of the DOC has said that “prolonged isolation is extremely negative,” at an April 10th, 2024 oversight hearing before the Committee on the Judiciary and Public Safety, and that, “….we do not practice solitary confinement….We do not have prolonged isolation in the DC jail.” Yet, someone who worked in the Department of Corrections as a case manager said, soon after, “I observed DOC’s frequent use of solitary confinement….” Because the Department does not provide the information to fully describe how often or how solitary confinement is used at the jail, what we know about its use is episodic: during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic April 2021, as many as 1,500 people in the DC jail were confined to their cells 23 hours a day in reaction to a COVID-19 outbreak. In response to oversight hearings in 2023, the DOC reported that, in 2022, there were at least two hundred instances where someone had been in restrictive housing for a longer stay of more than one month. After reporting most Freedom of Information Requests Acts on the topic were returned unanswered, the Council on Court Excellence reported data from DOC that, in 2021, “the average length of stay in segregated housing was 49 days.” Lawmakers are considering approaches consistent with legislation enacted in New York City and New Jersey that would require the DC jail to regularly report on the use of solitary confinement.

DC should have a hearing on its legislative framework to end solitary confinement.

Currently, seven members of the Council for the District of Columbia support the Eliminating Restrictive and Segregated Enclosures (“ERASE”) Solitary Confinement Act of 2023. ERASE would prohibit nearly all forms of solitary confinement for individuals incarcerated at institutions owned, operated, and controlled by the DOC. The legislation also limits the use of solitary confinement for people at risk of self-harm, mandates that all residents in a DOC facility receive at least eight hours of out-of-cell time a day, and charges DOC with providing residents mental health services any time they’re placed in prolonged confinement, medical isolation, or suicide watch. An oversight provision of the bill would require DOC to collect and publish data on the ongoing use of solitary, allow residents to file special grievances when solitary confinement is used, and potentially sue the agency if they have been subject to prolonged solitary confinement. Unlike the United States Senate, the Council of the District of Columbia has yet to hold a hearing on the ERASE bill. Eighteen organizations through the Unlock the Box DC coalition are working to encourage the Committee on the Judiciary and Public Safety to schedule a hearing on the ERASE bill.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

The ACLU of DC, the DC Justice Lab, and the Unlock the Box DC Coalition November 2023

The Public Purpose: The Graduate Journal of American University's School of Public Affairs March 2022

Council for Court Excellence March 2024

The Washington City Paper May 2021

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime December 2015

The US Senate Committee on the Judiciary April 2024

The Washington City Paper May 2024

Harvard Kennedy School – Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy June 2023